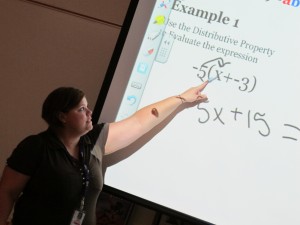

Jodie Mojzik, a math teacher at Washington High School in Indianapolis, leads a lesson.

A new state law that requires annual evaluations for Indiana teachers doesn’t take effect until the 2012-13 school year, but school corporations are already preparing staff for the changes to come. Teachers in six districts began receiving feedback this year as part of a pilot program designed to offer insight to the rest of the state.

Other school corporations are also ahead of the curve, trying to make the transition to state-mandated evaluations now so they’re not scrambling when August rolls around. For instance, in Starke County, the Knox Community School Corporation is offering teachers additional professional development materials.

Supporters of the new law say regular, consistent feedback will aid in professional development and make teachers more effective educators. But school corporations looking ahead say they have questions about how to conduct annual assessments and what the results will mean for teachers.

Elle Moxley / StateImpact Indiana

Students in Lori White's third grade class at Knox Elementary used problem-solving skills to design environments that answered the question, 'Would you rather live underground, underwater or in the sky?' During the activity, White encouraged her students to seek input from their peers and asked questions to check their understanding.

Lori White has spent her entire career in Knox — four years working with emotionally disturbed students, eight teaching the third grade. During a recent problem solving exercise, she walked from table to table, asking questions to check her students’ understanding.

White tries to give back — not just to her students, but to others. For instance, White and her fellow third grade teachers are donating their Scholastic Book Club points so every second grader in the district can take home a new book this summer.

But starting this fall, here’s what the state wants White’s bosses to quantify: Is she a good teacher?

Like most Indiana educators, teachers in Knox are worried. White says her colleagues fear efforts like their summer reading program won’t translate to paper when the district begins evaluations in the fall.

“They’re a little afraid,” White said. “‘What if I don’t show good enough evidence when they come into my classroom? Am I going to lose my job? Am I not going to get a raise?’”

Across the country, states are adopting new rules for evaluating educators. That’s a step in the right direction, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality.

“We’ve had systems for a long time that have included no objective evidence whatsoever,” says NCTQ Vice President Sandi Jacobs. “It’s been entirely subjective based on the principal or whoever the evaluator is, usually doing some sort of classroom observation.”

Too often, Jacobs says, the result was nearly every teacher in a district would be given the same satisfactory rating — and that means educators didn’t receive any real feedback on how to do their jobs more effectively. She says it’s encouraging to see more states move toward systems that hold teachers accountable for student learning.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Bennett says what makes Indiana different from other states who have implemented mandatory teacher evaluation laws is that the Department of Education hasn’t specified an assessment tool for districts to use. That keeps local control within individual school corporations, Bennett says.

“They’re a little afraid. ‘What if I don’t show good enough evidence when they come into my classroom? Am I going to lose my job? Am I not going to get a raise?’”

—Lori White, third grade teacher

Districts can adopt whatever model they want for completing evaluations, but they must meet the criteria outlined last spring by the Indiana General Assembly. Three Indiana school districts are currently piloting an evaluation system developed by the Department of Education — known as “RISE” — while three others are trying out their own methods. Bennett says feedback so far has been positive.

“The discussion around quality instruction has changed, and we have a much different culture about the discussion about how we better teach our children,” Bennett says. “We’re having a discussion we’ve never had before in this state.”

Bennett says anyone who disagrees with the new law needs to look at evaluations as a way to provide feedback to good teachers, not a method for weeding out bad ones.

Seven Teacher Merit Pay Questions, Answered

Peggy Shidaker taught French in Knox for 31 years before becoming the district’s Director of Curriculum three years ago. She says she never worried about evaluations during her teaching career, but she admits the state’s standards are far more stringent than the infrequent, informal assessments Knox has used for years. Shidaker has bought additional professional development materials to help prepare her teachers to be graded on the RISE rubric.

“Our teachers are going through a series of video explanations on how this rubric will effect them in the classroom, what they can do to meet the expectations of the rubric,” she says, adding that teachers are feeling more comfortable with the state’s evaluation system as they work their way through each module.

But both Shidaker and teachers say they’re still apprehensive about the provision of the law that links teacher performance to students’ test scores. The impact on a teacher’s overall rating varies depending on what data is available from the state, but for some educators, test scores will account for 35 percent of their evaluation.

Indiana State Teacher’s Association Vice President Teresa Meredith says while the ISTA agrees teachers should be held accountable for student learning, teachers in areas of high poverty or high need are at a disadvantage.

“You can be an amazing teacher consistently, and I think, based on the way particularly the RISE model is designed, there is great potential for negative impact to you, that you might not be rated as effective as you truly are,” Meredith says.

That impact of test scores will be greatest for teachers in grades four through eight, where ISTEP+ data is available. Educators in other grades and subjects will have to set student learning objectives — the state defines these as long-term academic goals — to score their own evaluations. Shidaker says she’s had trouble explaining these measures to teachers who don’t have test scores to fall back on.

Jake Skelly teaches physical education, aquatics and lifeguarding at Knox High School. He’s one of those teachers whose discipline falls outside prescribed state testing. He’s also the only teacher in Knox sitting in with a team of administrators as they receive training on how to evaluate teachers.

“Anytime there’s a chance or something new, it’s a little scary. There’s a lot of questions you ask,” Skelly said. “It’s a process. I think the state’s going the right direction as far as raising our expectations for instruction. This is just a tool to help that.”

Skelly said teachers in special related areas like physical education have a lot of questions about how they’ll be scored on the RISE rubric. But he says the professional development training Knox is offering its teachers has helped relieve some fears.

“You can be an amazing teacher consistently, and I think, based on the way particularly the RISE model is designed, there is great potential for negative impact to you, that you might not be rated as effective as you truly are.”

—Teresa Meredith, Indiana State Teachers Association

“I don’t think it’s an issue once you start looking at how the evaluation process works and what the purpose of it is,” Skelly said. “It’s not about the content. It’s not. It’s about the procedures involved. It’s about the instruction,” which should be quality in all disciplines.

Celine Coggins is founder and CEO of Teach Plus, a non-profit company which pushes to keep the most effective teachers in high-need schools. She says that when schools start teacher assessment programs, it’s important that there be a “buy-in” for educators — that they understand why their performance is being evaluated and how it can be beneficial to them.

That’s what Shidaker is trying to do in Knox. She says there’s no such thing as a perfect lesson and wants her teachers to see the state’s tool as a way to provide feedback they can use to reach more students.

Teacher Lori White sees it a different way: evaluations are coming, whether teachers want them or not.

“But I think that if we remain positive and we, you know, try to bump each other up and help each other get over it, I think we will make it through that, and we will shine because we care about our kids,” she said. “They’re the most important thing.”

Only three teachers in Knox declined the professional development the district is offering in advance of state-mandated evaluations. All are on track to retire this month.